Following the Footsteps of Divine Michelangelo: A Lifelong Admiration

- Trip And Zip

- Aug 22, 2011

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 14, 2025

Michelangelo Buonarroti stands as one of the most remarkable figures in the history of art — a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet whose work spans some of the most iconic creations in European culture. Across several travels to Italy, encountering his masterpieces in person provided a deeper understanding of his extraordinary versatility and unmatched talent. His work has also profoundly shaped the way I see and perceive art and creativity itself — not merely as forms of expression, but as acts of struggle, vision, and transformation, where technique and imagination converge to reveal something far greater than the materials themselves.

My first introduction to Michelangelo, however, came not through travel, but through the pages of a book — The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone. I first read it in my youth and returned to it repeatedly over the years. With each reading, new facets of Michelangelo’s personality and creative struggles emerged. The book provided not just insight into his artistic brilliance, but into the man himself — stubborn, driven, tormented, yet gifted with an almost superhuman ability to shape beauty from raw stone. That early fascination added deeper meaning to every encounter with his works in Italy, placing each sculpture and fresco within the context of a relentless pursuit of perfection.

Florence — The Masterpieces

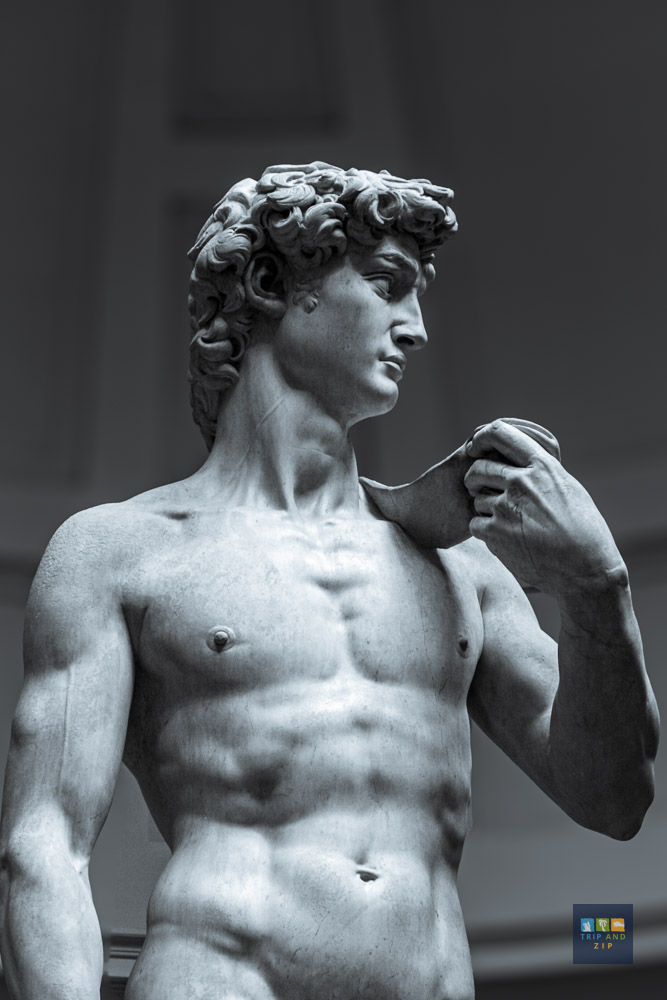

In Florence, Michelangelo’s work is inseparable from the city’s identity. At the Galleria dell’Accademia, David dominates the space, not only in scale but in presence. Seeing David in person is to witness the ultimate mastery of anatomy, tension, and symbolic power. This is not merely a biblical hero, but a universal symbol of human potential, frozen at the moment between contemplation and action, where every muscle, every sinew holds the weight of that decision.

The origins of David are as extraordinary as the sculpture itself. The marble block lay abandoned for decades, considered too flawed for any meaningful project. Yet Michelangelo saw potential in its imperfections, carving one of the most iconic figures in history from a material others had deemed useless. This ability to extract greatness from constraint, to see beauty where others saw limitation, defines much of his creative legacy.

The cultural and intellectual environment of Renaissance Florence, shaped in no small part by the Medici family, created fertile ground for artistic innovation. Art, philosophy, science, and politics intertwined, attracting not just craftsmen but thinkers, inventors, and visionaries. Michelangelo operated within this sophisticated and highly competitive environment, navigating the ambitions of powerful patrons while fiercely guarding his creative independence.

At San Lorenzo, the Medici Chapels house some of Michelangelo’s most evocative sculptural compositions. The tombs are adorned with the allegories of Night, Day, Dawn, and Dusk, figures whose physical beauty is infused with unease and tension. They represent not just the passage of time, but Michelangelo’s lifelong meditation on mortality, change, and human frailty.

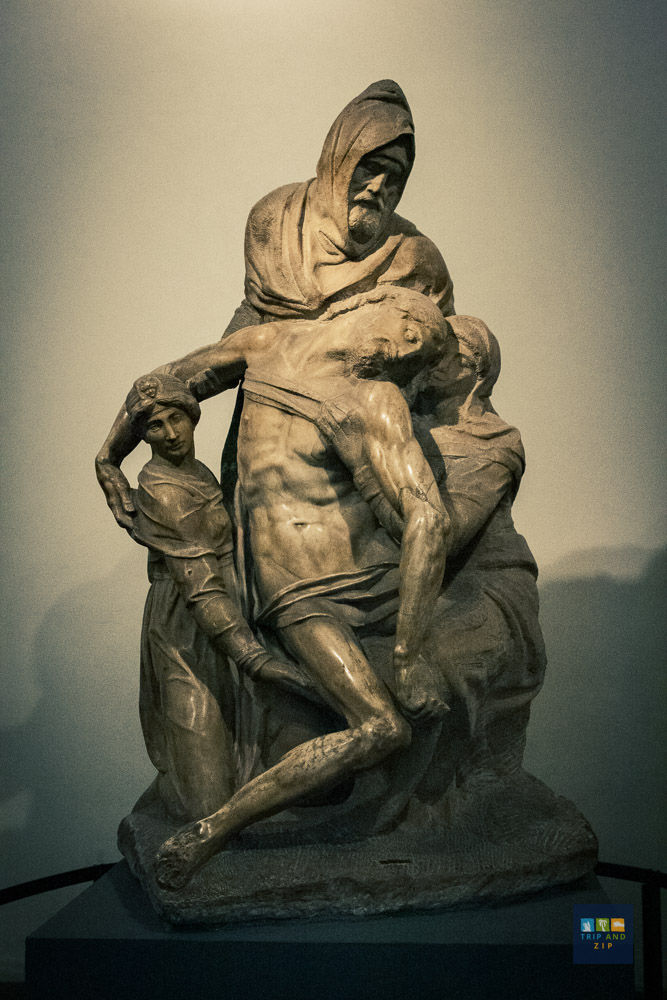

In the Duomo Museum, the Bandini Pietà — a later work — reflects these same preoccupations. In this unfinished composition, Nicodemus, often believed to bear Michelangelo’s own features, supports the lifeless body of Christ. Its raw, rough surface contrasts sharply with the polished perfection of earlier works, signaling the artist’s evolving focus on inner truth over outward beauty.

The Bargello Museum preserves further insights into his early development. The Bacchus, with its unsteady pose and wild gaze, captures both the excess and fragility of life. This rare secular work stands alongside other early pieces, revealing Michelangelo’s fascination with the dynamic tension between movement and form — a constant thread throughout his career.

Rome — Monumental Commissions

In Rome, Michelangelo’s creative vision expanded beyond sculpture into painting and architecture. At St. Peter’s Basilica, his Pietà remains one of his most celebrated masterpieces. Sculpted when he was only in his twenties, the work combines technical brilliance with profound emotional restraint. Mary’s serene grief, cradling the lifeless body of Christ, transforms religious iconography into a universal meditation on loss and grace.

Michelangelo’s architectural genius is also fully present in St. Peter’s Basilica, where he took over as chief architect later in life. His redesign of the dome — completed after his death — remains one of the defining elements of the basilica and a signature feature of the Roman skyline.

The Sistine Chapel offers Michelangelo’s most expansive creative statement. Beyond the ceiling’s creation narrative, The Last Judgment, painted decades later on the altar wall, presents a far more personal, unflinching vision of divine justice. Here, the idealized beauty of the ceiling gives way to turbulence — a swirling mass of muscular, twisting bodies caught between salvation and damnation. The overwhelming scale, complexity, and emotional intensity make it one of the most ambitious and revealing works in European art.

In San Pietro in Vincoli, the monumental Moses, originally intended as part of Pope Julius II’s tomb, stands as another masterwork. Every detail — from the tightly curled beard to the coiled energy in his limbs — captures Michelangelo’s ability to imbue marble with both physical presence and psychological depth.

Nearby, at Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, the Risen Christ offers a rare depiction of serene confidence, standing in quiet contrast to the more anguished expressions found in his other religious works.

Milan — The Final Work

In Milan, Michelangelo’s artistic journey comes to a touching close with the Rondanini Pietà, displayed at the Castello Sforzesco. This unfinished work, which Michelangelo was still reworking in the final days of his life, reflects his evolving approach to form and meaning. The figures of Christ and Mary seem to dissolve into the marble itself, merging abstraction and fragility — a stark contrast to the confident forms of his youth. The sculpture stands as a final meditation on death, redemption, and the limits of artistic creation.

A Legacy Across Disciplines

Michelangelo’s contributions extend far beyond individual works of sculpture or painting. His architectural projects, from the elegant staircase of the Laurentian Library in Florence to the ordered redesign of Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome, demonstrate his mastery over space, light, and proportion. His ability to shape entire environments with the same vision he applied to marble blocks or painted ceilings solidified his legacy as a universal artist — not confined to any single medium.

Across sculpture, painting, architecture, and even poetry, Michelangelo’s legacy stands as one of the most complete expressions of human creativity. His works bridge the human and the divine, capturing both the beauty and struggle of existence itself. To follow his path across Florence, Rome, and Milan is not just to trace the career of an artist, but to witness the evolution of an extraordinary mind — one that has shaped the visual language of European culture for centuries.

Comments