Florence: An Open-Air Museum of Sculptural Masterpieces

- Trip And Zip

- Aug 28, 2011

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 15, 2025

Florence has often been described as an open-air museum, and nowhere is this truer than when walking through its piazzas, where sculpture — ancient, Renaissance, and even modern — shapes the character of the city itself. Throughout my travels, I’ve often confessed my deep admiration and passion for sculpture, and Florence offers a setting where that passion is constantly rewarded.

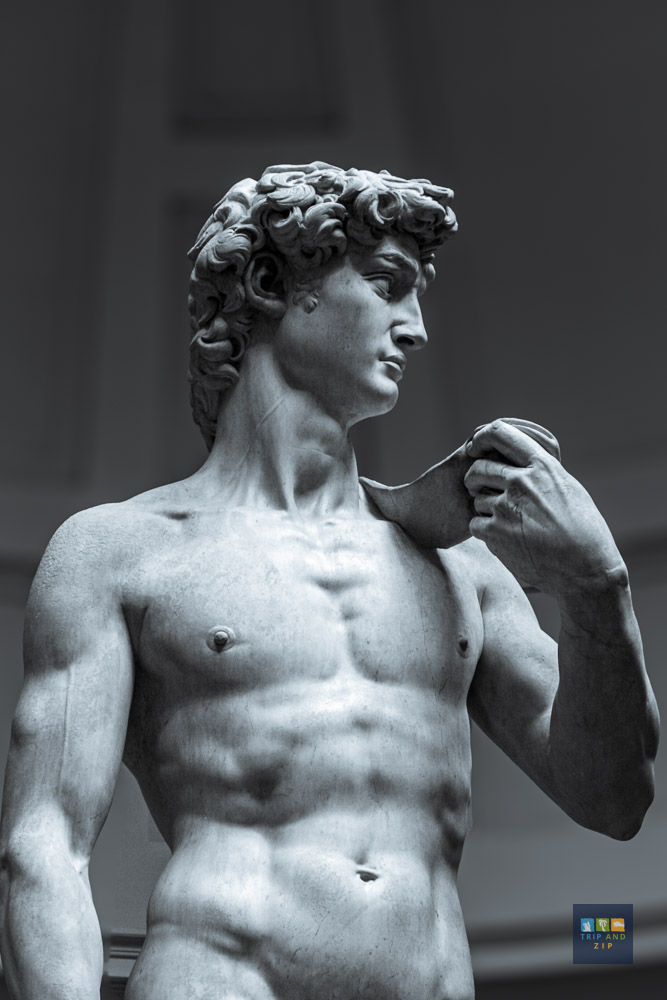

This post focuses specifically on the outdoor sculptures of Florence, showcasing the incredible works found in the city’s public spaces. As Michelangelo’s masterpieces have already been covered in a separate post, this is a chance to appreciate the broader sculptural landscape that helps make Florence such a remarkable destination.

The city owes much of its artistic identity to the sculptors who shaped its public spaces and defined Renaissance sculpture itself. Masters like Donatello, Verrocchio, Giambologna, Cellini, and Michelangelo left their mark not only in museums, but in Florence’s squares, loggias, and church façades. Their ability to blend naturalism with allegory, human emotion with classical ideals, and religious devotion with civic pride created a sculptural language that still defines the city’s visual identity today.

In the heart of the city, Piazza della Signoria serves as an unrivaled stage for some of Florence’s most iconic outdoor art. Here, the Loggia dei Lanzi, a 14th-century open gallery, displays a striking collection of Renaissance sculptures under its graceful arches. The Rape of the Sabine Women by Giambologna, with its dramatic spiraling composition, is a masterpiece of movement and emotion, while Cellini’s Perseus, holding the severed head of Medusa, exemplifies the Renaissance fascination with myth, allegory, and storytelling through the human form.

Just steps away stands Ammannati’s Neptune Fountain, where the sea god’s towering marble figure commands attention, blending mythology with civic symbolism — a reminder of Florence’s maritime ambitions and its mastery over water and trade. The surrounding figures, tritons and nereids, blur the line between decoration and narrative, a hallmark of public Renaissance art.

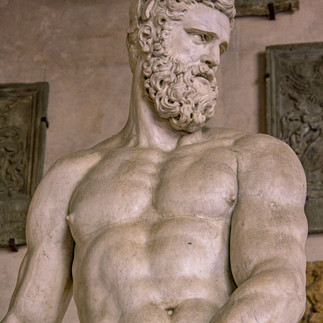

In front of Palazzo Vecchio, sculptures both original and reproduction stand guard. Michelangelo’s David once stood here, symbolizing the strength and defiance of the Florentine Republic. Today, a replica occupies the space, alongside Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, which offers a more raw, muscular vision of power and struggle. These pieces, some political, some allegorical, transform the piazza into a visual dialogue between art and power.

Public art in Florence is not limited to civic spaces. At Santa Croce, the tomb sculptures honor not just the dead, but the ideals they represented. Here, allegory blends with biography — poets, scientists, and artists resting under marble figures embodying virtues like knowledge, courage, and fame. Nearby stands the monument to Dante Alighieri, a figure eternally tied to Florence’s identity, his stern expression watching over the city that once exiled him.

Complementing Florence’s outdoor art is the Bargello Museum, an extraordinary treasure trove of sculpture and decorative arts. Housed in a former palace and prison, the Bargello offers a remarkable collection spanning from the early Renaissance to the Baroque, showcasing works by Donatello, Verrocchio, Michelangelo, and Giambologna. Its galleries allow visitors to trace the evolution of sculptural style, technique, and symbolism, further enriching the city’s reputation as a cradle of sculptural mastery.

Whether Renaissance masterpieces, modern interpretations, or treasures preserved in the Bargello, Florence’s public sculpture transforms the city itself into a canvas. Each work is not just a decoration, but a conversation between history, symbolism, and artistic mastery — a dialogue that continues to inspire my passion for sculpture, time and time again.

Comments